Cultivating creativity in chemistry

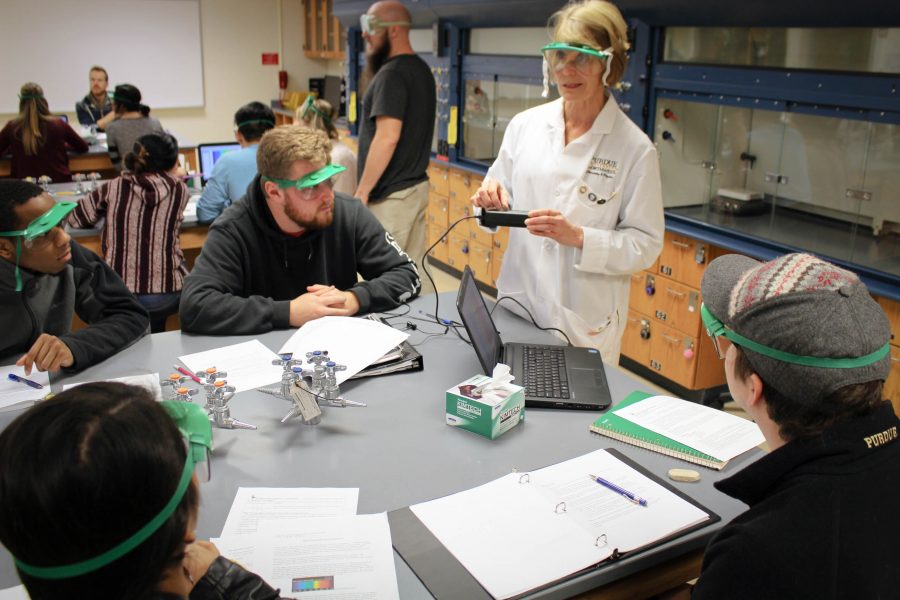

Kathryn Rowberg, associate professor of chemistry, gives a demonstration to her students.

With energy and enthusiasm, Kathryn Rowberg, associate professor of chemistry, incorporates art into her lectures to remind students that science does not always have to be serious business.

One of the ways Rowberg incorporates art into her lectures is by teaching a unit in her chemistry class that has the students create a Prussian blue color. The students and Rowberg talk about color theory and why one sees a certain color after mixing orange and yellow solutions. Afterward she has the students add an acrylic medium to the solution to create paint, and they make a painting.

“It’s great because they get their chance to be creative, using their left brain with high order thinking. Then they switch over and use their right brain for their creative side. Rarely do people say they got to have fun in science, and I think this is a nice way to incorporate it,” Rowberg said.

To give students another opportunity to think about how art and science can complement one another, Rowberg talks about cave paintings and testing metals in soap-based solutions to create layers of color.

“I take the big parts of science and put them into context where it has meaning and can be understood, but in a way that uses art,” Rowberg said.

Rowberg decided she wanted to go into teaching after being a math tutor in high school, a biology lab assistant in college and a chemistry lab instructor in graduate school.

“I always enjoyed the challenge of trying to explain science phenomena and determine what would make information ‘click’ for the students,” Rowberg said. “Being a professor is the perfect meld of helping students learn material and guiding them in independent research projects.”

After earning a doctorate’s degree in chemistry from the University of Illinois at Chicago in 1990, Rowberg moved to Northwest Indiana with her family and was unsure of what her next move would be. Having an interest in the law aspect of science, she decided to pursue a juris degree in environmental law at Valparaiso University. During that time, she began teaching at PUC.

“It was really hard to balance,” Rowberg said. “I had to be disciplined and jaded to carve out the time to do everything.”

Rowberg did not let her feelings stop her and pushed onward to finish what she had started. Her love for learning and science kept her motivated during that time.

“My whole family were science people, so I had an upbringing in that,” Rowberg said. “In college, I started taking science classes and I really liked the feel of it. It felt so alive, and once you get into chemistry it’s unlike anything else. You start to see how everything fits together and falls into place.”

Purna Das, head of the chemistry and physics department, said Rowberg’s dedication to her profession makes her a valuable faculty member to have in the department.

“She has a very warm personality and is very focused. I heard in my first semester as department head here that students flock to her office because they love her,” Das said. “She’s the person I turn to for advice when I need to learn something, and she’s very helpful.”

Das said this became obvious when he suggested the department make a recruitment video and Rowberg showed immediate interest and eagerness then volunteered to take on the project.

Hilary Vandervelde, freshman undeclared major, said Rowberg is a great professor.

“She gives so much respect to her students,” Vandervelde said. “She’s good at explaining things and walks around to make sure everyone understands the material.”

In Fall 2015, Rowberg also oversaw an undergraduate research project using infrared technology on legal document written on animal skin from 1750 left to the university by a professor. It was uncharted territory for Rowberg, but she welcomed the challenge.

The two students conducted analyses of the skin, learning that the two different colored inks on it were caused by a carbonaceous ink and an iron ink. After testing the calligraphy on the document, they used the infrared camera to see if there were carbon materials beneath the surface, as was common with documents of the era, and discovered it had three pence stamps on it.

“When we started with that camera, we didn’t know a thing about it,” Rowberg said. “It was such a great learning opportunity, and it’s fun when you have the privilege to look at a new area.”